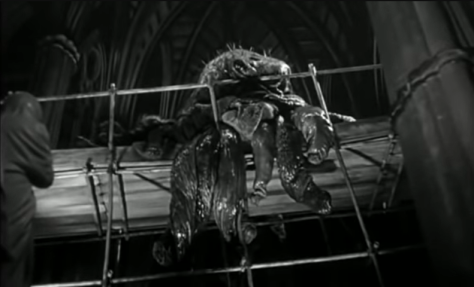

Released a mere nine months after the original King Kong in 1933 (this will post just two days shy of its eightieth anniversary), Son of Kong’s rapid turnaround leaves it in a bizarre place, a sequel that feels supplementary to what is probably the most important monster movie ever made. It has never been a particularly beloved movie, and despite the involvement of all the key people behind the scenes of the original—producer Merian C. Cooper, director Ernest Schoedsack, screenwriter Ruth Rose, and stop motion artist Willis O’Brien and his crew—one can detect how the rapidity of its creation rendered it a half-formed footnote (only sixty-nine minutes in length) even when it was new. King Kong inspired multiple generations of monster fans and left an entire form of storytelling in its wake—Son of Kong, not so much.

That hasn’t stopped me from being fascinated by this movie, because for all the ways it will forever toil under the shadow of its predecessor, it is historically important in several low-key ways, representing a major shift in the evolution of both King Kong and of monster movies as an idea: it is the point where the underlying sympathy for the monster comes to the surface. Now, this is a legacy that I’ve technically started writing about backwards, after I covered Mighty Joe Young last Christmas Apes season—that was the second movie by Cooper, Schoedsack, Rose, and O’Brien to take the sympathy they had built for Kong and rewrite it into a lighter story. As I argued there, this could come off as a commercial decision, but it also feels like a product of some phantom sense of guilt, and a desire to show that no matter how King Kong turned out, it is possible for humans and amazing creatures like Kong to co-exist peacefully, if they just got to know each other. What they would do with Mighty Joe Young begins in Son of Kong, but what’s particularly intriguing is, in the latter’s close proximity to the original Kong, it shows just how soon the original crew began to reconsider how a monster movie could operate.