Let’s return to the Showa era, and examine how the Godzilla series looked towards the youth in two different ways.

Continue reading Zillatinum: Part 3 (All Monsters Attack & Godzilla vs. Gigan)

Let’s return to the Showa era, and examine how the Godzilla series looked towards the youth in two different ways.

Continue reading Zillatinum: Part 3 (All Monsters Attack & Godzilla vs. Gigan)

Some nine years after It Lives Again, Larry Cohen returned to his monster movie debut for one final bow—but this was Cohen returning after expanding his repertoire and innovating in the genre in the eighties, first with Q – The Winged Serpent and then The Stuff, both classics in their own right. The increasingly over-the-top and comedy-infused styles of those movie do in fact continue in It’s Alive III—sometimes in very direct ways, considering the actors involved—keeping it in line with Cohen’s eighties filmography; at the same time, it develops many of the themes and emotional beats that made the original It’s Alive and its supplementary first sequel into something genuinely special. Yes, these movies about murderous mutant babies carry all the marks of schlock genius, but as weird as it sounds, they also have a heart, and that makes something like Island of the Alive stand out just as much as…well, everything else in it.

Continue reading It’s Alive III: Island of the Alive (1987)

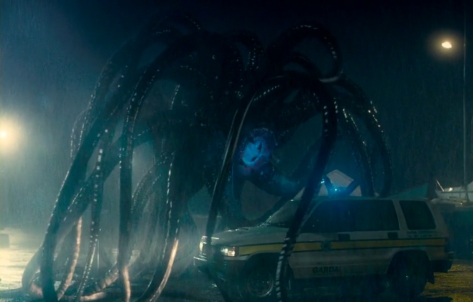

I’ve written about some wildly varying monster comedies, and one of the potential points of variation in them is just how seriously they take their monster—it is still possible for a movie to be a comedy while still presenting us with a monster that is threatening or even scary in a relatively straightforward manner. Alligator is a good example of that, as is Tremors—and the latter is the one that is the most apparent inspiration for the Irishcreature comedy Grabbers, where even the title seems to be a sly reference. The similarities run deep: both are rooted in a certain working class milieu, focusing on a group of small town personalities forced to do battle with a extraordinary menace, with the more ridiculous elements of their generally uneventful lives playing a part, good or bad, in the ensuing chaos; moreover, both are also indebted to classic monster movie traditions, and present those things without intentional subversion (but with inventive creature designs.) It’s an entertaining kind of light horror that doesn’t come around that often—with less overt cynicism or gruesomeness than most horror-comedies—and this one utilizes its setting and its ensemble to very good effect while getting an equal amount of juice out of its monsters.

Continue reading Grabbers (2012)

The popularity of the Godzilla films in their heyday did not just lead to homegrown competitors and imitators—as we saw with Yongary and Gorgo, film makers worldwide sometimes made their own attempts at similar monster material. I’ve written about that particular “Monster Boom” period pretty extensively, but a very similar pattern emerged following Pokémon, a later monster-based phenomenon that was clearly inspired by nostalgia for the original Monster Boom. That series’ thundercrack emergence in the late nineties led to a plethora of other media based on the idea of monster collecting and battling, especially in Japan, and I’ve written about some of those as well (you can also find a surprisingly deep recollection of even more Pokémon coattail riders in Daniel Dockery’s 2022 book Monster Kids)–but wouldn’t it be interesting to see how the basic ideas of a monster collecting franchise could be filtered through a completely different cultural lens?

This brings us to Monster Allergy, an Italian kids comics-turned-attempted-franchise that doesn’t outright announce its indebtedness to Pokémon and the other kids monster series of its era, but come on—it’s about “monster tamers” capturing monsters in small objects, and that alone makes the connection obvious. It’s certainly no rip-off, as any similarities largely disappear past those barest of surface elements, and instead follow more traditional western low fantasy storytelling. But regardless of the degree of intention, this does represent a very European take on some of Pokémon‘s core ideas, a kid-focused adventure in a monster-filled world, and In this way, it is to Pokémon what a Gorgo or a Reptilicus was to the original Godzilla.

The movies that get the tag “Science Gone Wrong” on here are part of one of the longest lineages in the history of creature features—and probably one of that history’s most reactionary undercurrents, demonstrating a ceaseless anxiety about scientific discovery and experimentation. The deeper we dive into the mechanics of nature, the closer we get to inevitably crossing lines we were never meant to cross, with terrible consequences the equally inevitable result—or, that’s the way they see it, and it’s a structure and theme that has never really gone away, and manages to adapt itself to whatever the latest technological and scientific advances (although by “adapt to”, I don’t necessarily mean “understand.”) Splice is a film that very intentionally hearkens back to some of the more hysteria-prone versions of that Sci-Fi narrative, and even places it in the consistently hackle-raising field of genetic engineering, which has been the topic of more than a few monster movies over the decades. The innovation here is that the lines being crossed in this story are not necessarily being done in the name of science, but something far more personal—and so the ensuing terrible consequences have some different and sometimes more disturbing dimensions.

How long has it been since I wrote about a yōkai movie? Clearly, far too long.

I’ve already written quite a bit about the long history of tokusatsu depictions of Japanese spirits and monsters, which bridge the traditional stories and the modern kaiju and kaijin material that take inspiration from them. Considering that deeply-rooted connection, you can understand why some tokusatsu production lifers would eventually choose to make something yōkai-related—and Sakuya: Slayer of Demons (Japanese subtitle Yōkaiden) is a prime example of just that. Director Tomoo Haraguchi’s “tokusatsu lifer” status is inarguable: he started out working on models and make-up as far back as Ultraman 80 in the early eighties, eventually working on to previous site subject Ultra Q The Movie and the the nineties Gamera trilogy (more recently, he has some credited design work on Shin Ultraman.) The movie he produced is a smaller scale project that showcases some of what classical effects could do in the new millennium, one set of traditions nestled within a story based on a much older set of traditions.

The Movie Monster Game, well, it’s a game about movie monsters. Released in 1986 (the same year as the even more famous giant monster game Rampage) for the Apple II and Commodore 64 and developed by Epyx, a company that gained a name for itself in the eighties PC game space with titles like Impossible Mission and California Games, it comes from a very different epoch than the previous giant monster-based game I’ve written about, a strange and experimental time when game design didn’t always have clear rules, and where a degree of abstraction was still present as a game could only convey so much visual information (Epyx’s earlier giant monster title, Crush, Crumble and Chomp!, a strategy game released in 1981, provides an even primitive-looking example.) Despite that, The Movie Monster Game actually shares a lot in common with later entries in this category, especially in the presentation–decades before War of the Monsters surrounded itself with a nostalgic metafiction wrapper, Epyx went even further, not just basing its menus around a movie theatre motif (complete with “trailers” for other Epyx games that appear before you begin playing), but structuring their game as essentially a movie you construct from various component parts pulled from numerous giant monster movies across the subgenre’s history. Even this far back, you can see that the artifice of these stomp-em-ups, and the context of the audience itself, was considered an indelible part of the experience.

That’s all well and good, but there’s a major advantage that The Movie Monster Game has that even later creature feature games could not pull off: alongside a group of “original” monsters that directly homage specific movies and tropes, they managed to officially licence Godzilla from Toho, putting the King of the Monsters prominently on the package for all to see, and making it the first video game released outside of Japan to feature him. Epyx was not an unknown company in 1986, but even so, getting the sometimes fickle Toho to lend out their star monster to an American game developer at that point still seems like a feat (it is equally surprising that they agreed to let Godzilla and Pals appear in the recent indie brawler GigaBash, a game that I still intend to play.) This was not long after the release of The Return of Godzilla (and its English release Godzilla 1985), which at least put it outside the lowest periods for the franchise, and leads me to believe that this collaboration was not an act of desperation–maybe they were just feeling generous. In any case, Godzilla’s fully approved presence in something with as definitive a title as The Movie Monster Game certainly gives it an air of legitimacy.

Released a mere nine months after the original King Kong in 1933 (this will post just two days shy of its eightieth anniversary), Son of Kong’s rapid turnaround leaves it in a bizarre place, a sequel that feels supplementary to what is probably the most important monster movie ever made. It has never been a particularly beloved movie, and despite the involvement of all the key people behind the scenes of the original—producer Merian C. Cooper, director Ernest Schoedsack, screenwriter Ruth Rose, and stop motion artist Willis O’Brien and his crew—one can detect how the rapidity of its creation rendered it a half-formed footnote (only sixty-nine minutes in length) even when it was new. King Kong inspired multiple generations of monster fans and left an entire form of storytelling in its wake—Son of Kong, not so much.

That hasn’t stopped me from being fascinated by this movie, because for all the ways it will forever toil under the shadow of its predecessor, it is historically important in several low-key ways, representing a major shift in the evolution of both King Kong and of monster movies as an idea: it is the point where the underlying sympathy for the monster comes to the surface. Now, this is a legacy that I’ve technically started writing about backwards, after I covered Mighty Joe Young last Christmas Apes season—that was the second movie by Cooper, Schoedsack, Rose, and O’Brien to take the sympathy they had built for Kong and rewrite it into a lighter story. As I argued there, this could come off as a commercial decision, but it also feels like a product of some phantom sense of guilt, and a desire to show that no matter how King Kong turned out, it is possible for humans and amazing creatures like Kong to co-exist peacefully, if they just got to know each other. What they would do with Mighty Joe Young begins in Son of Kong, but what’s particularly intriguing is, in the latter’s close proximity to the original Kong, it shows just how soon the original crew began to reconsider how a monster movie could operate.

Half Human (original Japanese title The Beastman Snowman) exists as a curious footnote in the history of Toho’s monster movies—it is Ishiro Honda’s direct follow-up to Godzilla (which prevented him from directing the actual Godzilla sequel also released in 1955), with much of that film’s cast and crew carrying over, including effects director Eiji Tsuburaya, story originator Shigeru Kayama, and screenwriter Takeo Murata (also the writer of Godzilla Raids Again and Rodan), which subsequently became an obscurity whose original Japanese release has never officially appeared on home video (although that doesn’t prevent people from finding it if they look a little.) Like Godzilla, this movie’s American incarnation was a heavy edit job, lopping off over over thirty minutes of run time, radically altering the story and tone, and inserting scenes of American actors like John Carradine (who probably wouldn’t turn down a movie role even if you paid him to) to make it seem less foreign, and that version has been the only one easily available all this time. There’s a reason for that pattern of unavailability that we’ll get to, but it has in some ways rendered this movie as much of a phantom as the Abominable Snowman at its centre, a missing link between Godzilla and the Honda-directed monster movies to follow.

Little Otik (Czech title Otesánek, sometimes referred to as Greedy Guts) is about bringing the punitive moral logic of old European folk tales into the modern world. In those stories, no macabre retaliation is too over-the-top for a perceived slight against universal propriety, any deviation from tradition or against common sense justifying a horrendous course correction inflicted on people guilty and non-guilty—to most people hearing those tales today, they come across as horrors whose purpose is hidden under layers of sadism. There is some darkly humorous joy to be derived from these things, with their distinct lack of proportion, and Little Otik even amplifies the surrealistic and disturbing aspects by couching its story squarely in one of the most vulnerable aspects of humanity: birth and parenting. As with most of the work of Czech stop motion animator and director Jan Švankmajer, who made this movie with design work from his wife and fellow surrealist artist Eva Švankmajerová, what we experience is an artistically impeccable nightmare.