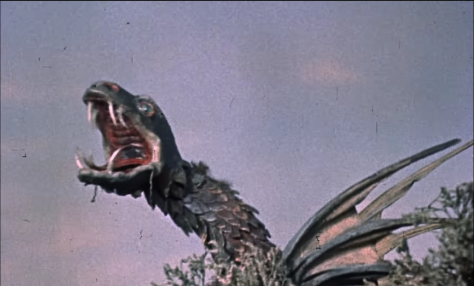

Early 1961 saw an unusual uptick in European-made giant monster movies: over two months, Gorgo and Konga premiered in Britain and elsewhere in the English-speaking world, while the Danish-made Reptilicus debuted in its home country. This represented a rather singular mad rush to cash in on the success of Godzilla and other Japanese-made monster movies, but it sputtered out as soon as it began, leaving us with only a few very odd attempts to recreate the kaiju film with different sensibilities. The rest of the world got their chance to partake in Denmark’s only giant monster movie after a year-long delay, as instead of simply dubbing the existing movie, our old pals Sidney W. Pink (acting as director and producer) and Danish expat Ib Melchior (as co-writer) essentially remade the movie, originally directed by Poul Bang, with most of the cast returning. The final product became rather infamous, ending up a modern Mystery Science Theatre 3000 punching bag and finding its way onto “Worst Movies of All Time” lists—by my estimation, it’s not even the worst Sid Pink & Ib Melchior movie I’ve watched, but there are definitely some issues that may be worth formally addressing.