Stumbling into something new while seeking out material for this site is always an exciting experience—and nothing demands my attention like the phrase “weird Yugoslav-Czechoslovak Science Fiction movie from the early eighties.” Visitors From the Arkana Galaxy (sometimes referred to by the more nondescript title Visitors from the Galaxy) is definitely a weird one, and has only found wide distribution in English-speaking countries in the last year thanks to Deaf Crocodile Films—its combination of unvarnished eighties European settings and borderline surrealist storytelling makes for the kind of cult-ready object that modern boutique film distributors regularly gift to us. Shifting between exaggerated reality and extreme fantasy, Visitors has something of a satirical edge, and combined with its bizarre visuals, you can really tell that director Dušan Vukotić comes from an animation background (the movie was partially produced by prominent Croatian animation studio Zagreb Film.) To further invite attention—my attention in particular—there is a prominent monster element that was designed and partially animated by stop motion animation master Jan Svankmajer before he gave us such classics as Alice and Little Otik.

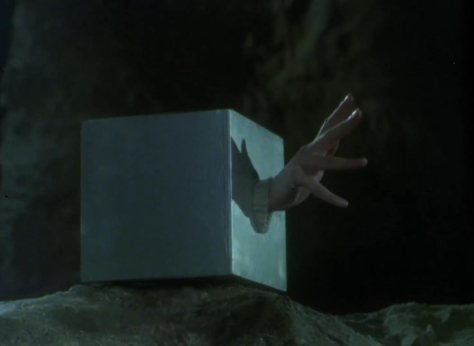

Opening with a blur of space age imagery and an enrapturing wash of seventies Sci-Fi synth by Tomislav Simović, the kind of music that embodies the style’s simultaneously unnerving and soothing qualities, the dreamy sensory experience shifts to the earthbound, where we meet aspiring Sci-Fi writer Robert Novak (Žarko Potočnjak), who can evidently only begin to craft his literary opus by putting on a space helmet and speaking passages into his voice recorder. In what turns out to be a story about the struggle of seeking one’s artistic dreams, Robert’s writing is interrupted by his neighbours—which includes a fellow artist, the aspiring journalistic photographer Toni (Ljubiša Samardžić), and his mother—and his girlfriend Biba (Lucié Žulova), who thinks he’s spending too much time with his fictional characters and not enough with the real people in his vicinity. There’s a bit of nuance to this depiction of an artist’s life: Robert’s need for escape is established not just through the people hectoring him while he writes (although he’s clearly also suffering from writer’s block as well), but from the scenes where we see his unfulfilling job at the front desk of a hotel, badgered by his boss and swarmed by the tourists that flock to his city. At the same time, Biba does have a point about his growing disconnect, and she is also shown to have her own issues (living in an apartment with her own set of annoying neighbours and an overprotective older sister), providing enough depth of detail to prevent her from just being a hectoring girlfriend. I do think she is allowed some hectoring, though, when his android creations from the planet Tugador in the Arkana galaxy—Andra (Ksenija Prohaska) and the child-like Ulu (Jasminka Alic) and Targo (Rene Bitorajac)—appear in the real world and, among other things, briefly transform her into a small cube.

Robert’s creations first contact him through his recorder, bringing him to a small island off the coast near his hotel job to find them. That first encounter is so disturbing to him that afterwards he visits a psychiatrist, and in conversation reveals that he possibly possesses the mental power of tellurgy, creating physical objects with his mind. This explanation ends up being as weird as the aliens: Robert tells a story of how, as an infant, he materialized working breasts on his single father in order to be fed. That establishes the way in which the aliens could become real, and soon Robert returns to the island with Biba just to have proof that he is not going insane, and both witness Andra experimenting on the island’s lone security guard by removing his heart, followed by all the business with the cube.

You can probably tell that there would need to be a very careful handling of tone to keep this series of baffling events from going off the rails, and to its benefit, Visitors finds that balance, mostly by varying the comedy. Sometimes, the humour comes from normal people somewhat realistically reacting to unbelievable events, while other times both the “normal” people and the Sci-Fi elements are equally absurd. The latter is frequently deployed with every human character other than Robert and Biba, who are regularly portrayed as cartoonish buffoons who react to the alien presence with numerous bizarre assumptions—for example, when all the tourists at the hotel decide to track down the extraterrestrial trio on the island, one woman convinces the rest that only way to show the aliens that they “have nothing to hide” is to take off their clothes, leading to moments of very European comedy where it’s just a crowd of stark naked people walking around a cave.

For the most part, Andra just wants to hang around with Robert in order to learn about human emotions—eventually she shows up in his apartment and begins vacuuming the floor with her arm (one of the more whimsical moments of Svankmajer stop motion)—and that inevitably causes problems for Biba, especially after she walks in on them touching each other, making the background erupt into orgasmic green static. From the beginning, it’s not hard to figure out why Robert thought up Andra in the first place, and any concern he has with his creations mucking up his real life is pretty quickly put aside when the benefits make themselves clear. Robert and Biba fight over this, but neither is truly made out to be totally in the wrong. If anyone comes close to being an antagonist in this story, it’s Targo, an aryan-looking little cretin who apparently took exception to Robert’s decision earlier in the movie to remove him from his novel and replace him with a monster named Mumu, at the behest of his book seller friend who tells him that readers want scary stuff (the author they keep bringing up as a point of comparison has the amusing name “Hover Decklerd”, who I don’t think is real?) So, for the rest of the movie, when he isn’t chasing after people in his spherical blue space vehicle, Targo is finding opportunities to summon his monstrous replacement to terrorize people—it starts out in the form of a small toy, because Robert had the idea that the monster should be “some insane toy” (an idea dismissed by his friend for being too cutesy I guess), and then grows into a person wearing perhaps the most indescribable monster costume you’ll likely see. It is abstract art come to life, like a fusion of HR Giger and the expressionist movie posters from Europe that you see posted online from time to time, unique and disgusting in such a way that the fact that it’s an old school person in a monster costume simply doesn’t register. While this obviously means that Mumu is not purely a creature of Svankmajer’s nightmarish animation like Little Otik, he does provide suitably horrific flourishes for certain shots, like a pair of eyeballs that pop out of its pectorals. For something that is obviously not a big budget affair, its combination of somewhat tongue-in-cheek cheesy Sci-Fi visual effects and genuinely imaginative ones matches the tone of the movie, and can even be held up as something that feels genuinely otherworldly at times.

The monster makes only fleeting appearances throughout the movie, giving a chance to look at its bizarre design but never long enough to see it actually do anything, but it gets to be front-and-centre in the climax, where Targo’s machinations lead it to break into a wedding party in Biba’s apartment. This is a very long sequence, escalating destruction and borderline horror moments that are intentionally undercut with gags—a man has his head torn off, and another’s head is flattened into a rubber dummy, but both treat it more like an inconvenience. The implication throughout this extended monster rampage sequence is that Mumu is not actually violent in nature—at first, it seems more interested in using its fleshy proboscis to sniff flowers—and that is probably the way Robert himself imagined it. However, as it is attacked by the terrified onlookers, it either defensively or even accidentally maims and kills them in response, the result of its strange alien anatomy (it burns down a room with flamethrower breath just so it can dislodge a fork in its throat.) The guests at the party argue over whether to shoot the creature or try to make peaceful contact with it, neither approach getting them anywhere—in attempting to make friendly gesture, the psychiatrist from earlier in the movie has his hand chomped off by a toothy stomach-mouth in a moment that presages a certain famous horror effect in John Carpenter’s The Thing, released not long after this. The whole sequence, while offering the exact kind of violence and thrills that Robert was encouraged to put into his novel, is actually more a comedy of errors.

The shifting, borderline contradictory nature of those moments brings us back to the way this movie handles Robert’s creativity. What little we hear of his novel seems mightily cliched—aliens coming to Earth to learn deeper truths from our primitive civilization (that beings like Targo view entirely with disdain) is certainly not award-winning material, and even the idea that a man disappointed by life would imagine a beautiful robot woman that dutifully loves him shows Robert to be pretty basic. But even though he willingly tries to change his story to match the tastes of mainstream readers, there’s a naive purity to his imagination, a desire to explore a universe full of interesting and well-meaning beings. In his vision of reality, it makes sense that the monster would not be as nasty as it appears, and that there would be hyper-convenient time-rewinding power that allows them to undo all the horrific damage his tellurgy might have accidentally caused. Robert is someone who uses his imagination to make something that is nicer than what he has, and it’s no surprise that the movie ends with him going back to the Arkana galaxy with his alien creations—giving halfhearted promises to Biba that he might come back at some point—finally finding a place where he can live out the fantasies he’s been crafting. Abandoning everything and everyone to live out his fantasy is not a choice that necessarily reflects well on him, but in that way it accurately reflects both the positive and negative aspects of spending so much time in your own head.