While a TV anthology series like The Outer Limits gives me enough classic monster-based material to be featured in an entire series of posts, its more famous contemporaneous counterpart, The Twilight Zone, did not dip into that well frequently enough to justify a similar treatment. However, among the few times Rod Serling’s influential fantasy vehicle did feature a monster story, it ended up being one of the most famous monster stories of recent memory, remade, parodied, and referenced endlessly for decades. That seems like a fair trade-off.

Originally airing on October 11th, 1963 (less than two weeks after The Outer Limits’ “The Architects of Fear”) as part of the series’ fifth and final season, “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” is one of those stories that ingeniously finds a way to make a monster attuned to the terrors of modern life—not just in its choice of setting, but in the anxieties that the setting provokes in people. That’s not as easy as it sounds, and one of the reasons you know that this one succeeded, tapping into something truly universal, is that its story is still completely understandable, if not relatable, sixty years later. While lots of little things about the miraculous and terrifying reality of commercial air travel have changed significantly over the years, in the end there’s still the stark reality that we’re stuck in a claustrophobic tube with no exits, and there is only a few layers of glass and metal that separates you from an unfathomable height. It doesn’t take much for a traveller to remember all the things that can go wrong there, realizing that technology can be as fragile as the frayed psyches entrusting their lives to it.

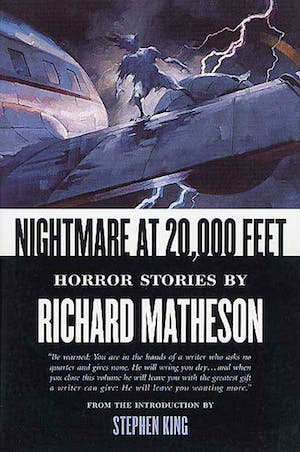

There are three different versions of this story in existence—minus all the aforementioned parodies—and the one person connecting all three is Richard Matheson, one of the most prominent and lauded contributors to The Twilight Zone and one of the most influential genre writers of his time. Matheson’s decades-long career spanned categories and mediums, and included singularly important pieces like the revisionist vampire novel I Am Legend, which, funnily enough, ended up being heavily influential on zombie stories. The first version of “Nightmare” was Matheson’s 1961 short story version, which he then adapted two years later into the Twilight Zone episode famously starring a pre-Star Trek William Shatner and directed by future Superman and Lethal Weapon director Richard Donner, and then personally adapted it a second time as a segment of the 1983 Twilight Zone movie directed by Mad Max mastermind George Miller and with John Lithgow in the lead role. As one would expect, Matheson maintained what ended up being the most iconic beats of the story across all three, changing mainly the atmosphere surrounding its lead, and the intensity of its nerve-wracking psychological tension.

As an author of horror, Matheson had a relatively straightforward approach, not afraid to dive into tried-and-true territory, but nonetheless finding the psychological and literary angles that changed their context and made the stories resonate anew. You can see this in the story “Duel” (which was later adapted as a TV movie helmed by a pre-fame Steven Spielberg), which in some ways feels like the “Nightmare at 20,000 Feet” of the highway—it has a hunter-and-hunted structure and an antagonist whose mostly faceless nature turns it into a pure survival narrative, but in its harried workaday protagonist and the use of the open road and the big, dehumanized vehicles populating it, it becomes something crafted specifically to the fears about driving along long stretches of near-empty highways and the way the nature of that activity keeps us separated and paranoid. Paranoia is, of course, an important part of “Nightmare” as well, putting a psychologically damaged individual in a situation where their sanity is questioned, but also where the line between fear-induced hallucination and reality is also the line between life and death.

While all stories centre on a man dealing with anguish and fear, the short story and the movie version maybe focus on the phobia more broadly, and sometimes more viscerally—in the original story, it is made clear that the protagonist is not just afraid of nearly everything (and fantasizes about the plane falling apart in mid-flight), but has flirted with suicide in the past, which is why he has a gun with him; meanwhile, Lithgow’s twitchy version of the character is someone nearly dominated by his phobia, and even among stories about people dealing with mental illness, seems like the one who would be the easiest to push over the edge. Shatner’s portrayal is the most grounded and sad, playing the protagonist as a man recovering from a mental breakdown and flying with his generally supportive wife—he has clearly suffered, and (as we are told during Rod Serling’s introduction) it was the stress of airplane travel that gave him a panic attack so violent that he spent several months in a sanitarium, but he ostensibly has a support network that the other versions of the character do not. He also has the most reason to be questioning his own grip on reality as he looks out his window and, as we know, sees a man on the wing of the plane—the image of it is, by all accounts, impossible.

The nightmarish quality of the creature doing its thing—floating to and from the wing like a dandelion seed on a breeze when it most inconveniences the witness—is almost equalled by the nightmarish quality of being surrounded by people that probably think you’re crazy. Shatner believably conveys the frustration and anxiety at even the way his wife attempts to placate him (he even calls out her condescension), let alone the stewardess and other people around him who have less reason to patiently endure his outbursts. There’s also something uniquely tense about the fact that the protagonist can “escape” from this horror by ignoring it, keeping the curtain down (in the short story and movie versions, we also see him try to avoid his fears by locking himself in the restroom) or taking his sleeping pills, but the possibility of avoidance only makes the possibility of real danger feel like an urgent moral choice. While the fear of flying aspect, and the monster itself, are probably the terrors that are meant to stick with audiences, the idea of no one listening to you and putting your whole perception into question might be the the most deeply unsettling element of the story, especially in the more humanistic TV interpretation.

The TV version also adds a reference that connects it to existing folklore, making it more explicitly into the kind of revisionist take that Matheson specialized in. Shatner refers to the “man” as a gremlin, and even briefly alludes to how the idea comes from stories pilots told during “the war”—indeed, the idea of little unseen monsters tampering with airplane tech did originate in World War II, making it a fairly modern when this originally aired. Gremlins are a good example of true modern mythmaking, creating imaginative supernatural entities that provide an “explanation” for some aspect of our lives we don’t fully understand, in the same way the various fairies, goblins, and sprites made sense of certain phenomena in their own historical context. In the war, gremlins were essentially mythologizing the prevalence of deadly technological failure in the age of aerial combat, and in “Nightmare”, Matheson transplants the idea to commercial air travel. Considering that this connection is not made explicit in the other versions, I wonder if someone on the series, maybe Rod Serling himself, suggested it in order to give the story an additional bit of cultural resonance.

Of course, the original Twilight Zone incarnation also has by far the silliest-looking version of the monster, with stuntman Nick Cravat wearing a woolly jumper to go along with his pug-nosed mask—it works fine in the moment when the gremlin plants itself right in front of the glass and stares at Shatner, but it’s not nearly the level of sinister the story might be going for. Maybe the less scary monster costume inadvertently communicates a strangely child-like demeanour for it, its potentially disastrous investigations of the wiring inside the wing coming from thoughtless curiosity rather than active maliciousness—although the way it very openly hides when the witness to its fun tries to get someone else to look tells another story. In any case, there is a dream-like quality to the gremlin as it prods and messes with the wing’s external and internal parts—that atmosphere was emphasized in the short story as well—and its weightless unreality makes its appearances strange and haunting in all versions. This feels like it comes from some perceptive observation: I am pretty confident that most people experience at least a slight disconnect when looking outside a plane in mid-flight, which is so high up and moving so fast that the outside world stops feeling “real”—and that disconnect also plays into the protagonist’s struggle with his own mental stability.

Needless to say, the bump in budget and technology allowed the movie version to portray the gremlin as something more demonic, maybe to a pointedly over-the-top degree—it better resembles the creature described by Matheson in the story, sure, but it more closely resembles the grotesque puppet monstrosities found in horror movies throughout the eighties. There is nothing approaching innocence in this monster, a toothy maniacal grin on its grotesque face as it tears up the wing and taunts Lithgow. It is a being of ill intent from beginning to end. Miller goes for the wild and stylized in his segment, with the monster framed by a raging thunderstorm and Lithgow’s bouts of hysteria played to the hilt—he has chosen to make his whole version a representation of panic itself, loud and frenzied and prone to only short moments of calm in between outbursts. This fits well with the “updates” Matheson has brought into the story, supplementing Lithgow’s fear of flying with the increasing number of ways that flights had become more irritating, and how fellow passengers seem antagonistic or giddily enforce rules that hamper your self-medication…to think, by 1983, smoking was being discouraged on airplanes! There was always an element of that in the story—the flight attendant’s attempt to be diplomatic about the protagonist’s claims is partially to prevent a panic from breaking out among the other passengers. They are trying to protect the safety and comfort of others, while our lead is trying to save their lives.

All three versions end similarly, and while they do frame our protagonist as a heroic figure, overcoming his own fears and risking his life to save everyone else, the conclusion is not so simply triumphant. The original story and the TV version are the closest, with the protagonist successfully shooting the gremlin from the open emergency exit, and as he is being carted off on the landing strip, he knows that he will be vindicated when other people see the damage the creature did to the wing—ultimately, he has reason to believe that he has retained his sanity, even if others around him don’t think so (“Nuttiest way of trying to commit suicide I ever heard” says a paramedic at the arrival point, a line that has even more punch in the short story.) In the movie, Lithgow is not given the satisfaction of killing the monster, as it gleefully dismantles his gun and makes a dramatic exit just as the plane is about to land, and while the gremlin’s destruction is discovered, it seems like the catharsis is not so much about proving his sanity, but in just getting off the plane and back to solid ground. Insane or not, getting out alive is the victory that really matters.