Maybe not surprisingly, I often determine Creature Classics subjects by asking the question “How often does this get ripped off?” Sometimes it’s not even in terms of ideas, but visuals—and you know you’ve struck some kind of nerve if disparate bits of culture liberally borrow your visual style for years afterwards. I think that’s more of the case with the original 1987 Hellraiser: not many people are doing their own take on the movie’s sadomasochistic themes, but they sure love all those chains and the stylishly leather-clad & mutilated demons that serve as the movie’s monster mascots (yes, even kids cartoons have taken a cue from them.) But, really, the visuals of those monster mascots in their first appearance—let’s just ignore the rest of the disjointed franchise, it’ll save us all a lot of time and a lot of headaches—are tied directly into that theme, creating a sui generis horror aesthetic based in the discomforting interweaving of extreme physical sensations, blending sex and pain in a way few other horror movies do, even when they are otherwise filled with both.

As previously mentioned in the Rawhead Rex post, the fallout of that movieleft Barker with a desire to write and direct adaptions of his work, and he was able to finagle that responsibility the next year with the adaptation of his 1986 novella The Hellbound Heart. Although still working on the lower end of the budgetary spectrum—one million dollars at the time—Barker and his effects and art direction crew pulled together something very distinct. Primarily set in an old house, its interiors carry the graying colour of rot in every room, a foreboding degeneracy that seems to infect every other location. The rot in the structure reflects the rot of the presence that haunts that house: world-trotting pervert Frank Cotton (Sean Chapman), a man so bored with mortal gratification that he tracks down a mysterious lacquered puzzle box—called the Lemarchand Configuration in the novella, after the mysterious toymaker who crafted it—in order to ritualistically call upon another, rumoured world of unknown ecstasies. When the puzzle box is “solved”, he summons those leather-clad monster mascots, the Cenobites, who initiate Frank into the club: a place where pain and pleasure at their most extreme co-exist, and where violent agony is the name of the game. In the novella, Frank’s introduction is to gradually have every feeling in his body heightened to the point of becoming entirely overwhelming; to make the movie a more visual experience, we are instead introduced to Hellraiser‘s trademark hooks, which proceed to tear him to pieces for the Cenobites to mess around with. In either case, Frank was not quite ready for the experience.

In both the novella and the movie, the Cenobites are introduced early, make an impression, and then sit out for a large portion of the story. In text form, the Cenobites are described in ways that emphasize their surrealistic qualities as much as their ghoulish imagery (one of them wears a belt made of tongues); on film, this is translated into their Gothic laceration fetish look, each one cut up and reconfigured in ways that shoot past horror and monster movie cliches and into their own unsettling zone, while the aesthetic of their world (lots of geometric objects with body parts nailed to them) looks like a conceptual art abattoir. In both versions, though, one of the Cenobites is described as having rows of jewelled pins patterned across their face, a visual that would prove to be the film’s most iconic when applied to actor Doug Bradley, who would go on to become one of the recurring horror movie characters—but in the beginning, he’s just one of the gang, and the name “Pinhead” is never spoken, only appearing in the end credits (where it was clearly meant as a joke—I mean, one of the others is named “Butterball.”) Their early, brief appearance leaves you wanting to learn more about them as the bulk of the plot takes place with the threat of their existence haunting every moment.

These entities are, at their heart, a new take on the sorts of deal-making demons that have been a major part of fantastical legends for centuries, and the story of Hellraiser is a modern re-imagining of that genre of Faustian bargains—but rather than having a character seek out a demonic source of riches or immortality, Frank instead wants something simultaneously higher and lower in scope. As we saw with the other two Clive Barker monster movies, as a writer he has always pursued horror based in dark desires, whether that be the gleefully primal immorality of “Rawhead Rex” or the alluring freedom of monsterdom in Nightbreed, and in this, the story that helped make his career, he shows people who are willing to go to dark places to get their rocks off (the same concept explored in the previous year’s From Beyond.) That seems like a base thing, but it’s probably more true to life. He recognizes the sometimes disturbing thin line between sex and violence, and essentially creates a whole new demonology to represent that, where all the demons wear slick S&M gear with fetishistic rips, tears, and incisions in the flesh. These “explorers in the further reaches of experience”, as not-yet-Pinhead calls them, look at the body as a place to experiment, and as far as we can tell, it’s the logical conclusion of whatever Frank was getting into before. The violence their victims are subjected to is not just typical eviscerations, but something more specific and disturbing, skin ripped and folded in discomfiting ways.

While the Cenobites take a long vacation from the story after those initial scenes, there’s still a monstrous presence to keep this in Creature Feature territory: Frank himself, who becomes a monster while trying to escape the other monsters. The house where Frank summoned the Cenobites and was taken to their torture dimension is eventually occupied by his brother Larry (Andrew Robinson)—who is named Rory in the novella, a name that I guess the movie studio thought was too British?—and his wife Julia (Clare Higgins), and during the move, Larry badly cuts himself on a protruding nail and bleeds on the floor of the room where Frank solved the box, the blood giving Frank a doorway to re-enter this dimension. In the novella, it’s given a more bodily edge, as its a mixture of the brother’s blood with Frank’s lingering jism that creates the opening, but the moments of the movie where the slowly recomposing body of Frank pieces itself together (a gooey effect apparently made by reversing footage of a melting wax sculpture) is memorably macabre in its own way. The shambling, skinless abomination Frank has become (played by Oliver Smith) makes contact with Julia, begging her to give him more blood so he can keep rebuilding and then flee before the Cenobites come back—she agrees despite her fear, because as we learn, she had cheated on Larry/Rory with Frank before their marriage, and that sex was apparently so good she is willing to do what her half-dead ex-lover says to get back to it.

In both versions, you sort of understand where she’s coming from. In the book, Rory comes off as nice but sort of milquetoast; in the movie, Larry and Julia have the sort of passive-aggressive rapport that can only come from a married couple who probably shouldn’t be one. Julia hates moving to Larry’s childhood home, hates being around Larry’s friends, and really, just hates Larry. Her short time with his bad boy brother probably left an indelible mark on her—in more than one way, because it’s clear that while a great lover, he’s also violent and abusive, which is something she seems to be into (Sean Chapman’s voice has a real commanding quality that sells before his domineering and alluring side.) There’s more excitement in one than the other, and to get that excitement back in her life, she begins to lure unsuspecting, bar-dwelling Yuppies into the room so she can murder them and let Frank suck out their juices. In another touch that emphasizes the visual horror, Julia trades the knife she uses in the novella for a hammer in the film, a much blunter (in both ways!) tool for murder. The first time she kills an unsuspecting if morally loose dope, she is terribly distressed by the ordeal—but the more she does it, the less she is bothered by it, and learns to savour the erotic thrill of bloodletting.

The one who ultimately unravels these supernatural goings-on is Kirsty (Ashley Laurence), and she’s one of the more interesting adaptations Barker makes from the source material: in The Hellbound Heart, Kirsty is another one of Rory’s friends, who has a unrequited crush on him, while in Hellraiser, she is changed to his adult daughter from a previous marriage (it’s implied her mother died in childbirth, leading to some recurring nightmare imagery she encounters.) In both versions, we are made to feel for Kirsty as a somewhat put-upon individual, with Julia regarding her with an indifference bordering on contempt while she responds silently in kind—she’s the innocent figure to contrast Julia’s moral indiscretions. I kind of found her relationship with Larry in the movie…interesting…as the closeness between daughter and father bordered on disturbingly needy, even if it is somewhat justified by the implied tragedy with her mother. It also adds another perverted layer to Frank, who in both versions takes an immediate attraction to her, which is far more disturbing when it’s his niece than when it’s his brother’s friend, and his lascivious pursuit of Kirsty is used in the final act to show how little he actually cares for Julia outside her immediate usefulness to him.

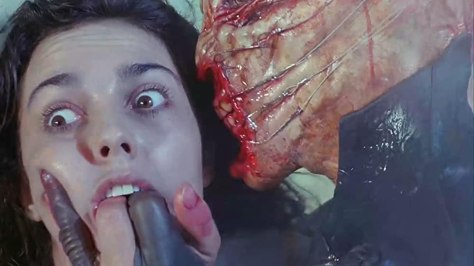

Kirsty is the second person to solve the Lemarchand Configuration, bringing the Cenobites back into the picture—which in the movie leads to a scene with a bizarre hallway and an even more bizarre scorpion-tailed monstrosity that chases after her. The Cenobite gang comes to take her, but she convinces them that she can deliver them Frank, which interests them far more; in the novella, the Cenobites are a little belligerent about people summoning them, but seem at least a little fair, while they have a more arbitrary way of bargaining in Hellraiser, which maybe emphasizes their demonic otherness a little more (they are “demons to some, angels to others”, but sometimes they can also be jerks.) Things get complicated in the climax when Kirsty discovers that Frank has murdered his brother and is now wearing his skin (the movie does show her being genuinely horrified by this in a way the novella doesn’t), but she succeeds in getting him to acknowledge his identity, giving the Cenobites the evidence they need to give him a second hook job. Novella Kirsty escapes from the house without much issue after that, while movie Kirsty is forced to fight off the Cenobites, who decide they’d rather get two souls in one visit—rather similarly to Rawhead Rex, it ends with a light show battle against monsters, because apparently Barker of the eighties thought that was the way to end a movie. Kirsty’s movie boyfriend, not really a major presence in the story until he reappears at the end, takes the sudden appearance of S&M demons rather in stride.

Hellraiser ends on a recursive note, with a mysterious vagrant who made multiple appearances early on to bother Kirsty turning into a dragon skeleton(!) and reclaiming the puzzle box, and we end on a scene of the merchant from the beginning of the movie handing it over to another intrepid pervert. Demon stories do generally imply that the evil represented by the demons are meant to be a constant, a thing that can be warded off but never defeated, and in this case that carries a meaning more specific than just a broad conception of evil. The Cenobites are the dark heart of humankind, a desire that many move towards without necessarily knowing it, while a select few who feel that the only worthwhile experience remaining is the pain-pleasure mixture that comes out of that box. That is a different sort of morality than the usual demon story, and it’s one of the reasons why Barker’s world is so innovative and fascinating.