It is 1953—the space race hasn’t even started yet, and no one has ever been sent into orbit. In Britain, you turn on the telly and see the first humans ever to visit space, put there by an independent science group. That group loses contact with their astronauts, and then learns that they will crash down in the middle of the country. Three men were in that rocket when it launched; only one is there when it returns to earth, and he has been irrevocably changed.

I’ve written about the work of Nigel Kneale before, sometimes directly and sometimes only in regards to other things, and while he is known primarily as a UK television writer, he was also one that had a profound impact on science fiction—and horror fiction—in the fifties and beyond. This began with his 1953 BBC serial teleplay The Quatermass Experiment, which introduced his self-possessed, problem-solving scientist hero Bernard Quatermass. Considered singularly thought-provoking and terrifying when it originally aired, it gave Kneale the clout to continue to produce more more well-regarded Quatermass serials, as well as other relevant-to-me subjects like The Creature (aka The Abominable Snowman), among a plethora of television projects. It also got the attention of a little-known movie studio called Hammer Films, who bought the rights to make a film adaptation of the story in 1955, and in the process changed its name to The Quatermass Xperiment (except in North America, where it was called The Creeping Unknown), a nod to the fact that its horror content would certainly lead to an X rating from British content regulators (they would repeat that joke a year later for X the Unknown, a movie that they initially hoped would feature Quatermass, before Kneale refused the rights.) The film was also a success, and it gave Hammer the idea that maybe science fiction and horror movies were a business they’d like to get into.

Famously, Kneale hated the fact that Hammer recast his very British vision of Bernard Quatermass, played by veteran actor Reginald Tate in the TV serial, as a gruff American scientist, played by film noir regular Brian Donlevy. He had other issues with the way they changed the script, but mostly he was bitter about the BBC owning the rights to the original serial and not paying him for the adaptation. As it turned out, the only real consequences of those disagreements was that Kneale would write or co-write all the other adaptations himself—including the two Quatermass sequels and The Abominable Snowman—which led to consistently good films. Unfortunately for Kneale, despite viewing his own version of Experiment as the definitive one, the BBC’s decision not to keep recordings of four of the six episodes of the serial (this was back in the days when teleplays were broadcast live, and the original airing even suffered from some technical issues) means that the only complete filmed version of the story is Hammer’s Xperiment.

The story in both is the same: Professor Bernard Quatermass and his rocket group (a British-American cooperation in the movie) have successfully sent three men into space, but things inevitably go wrong. The rocket crash lands in the English countryside, and they go to see the fate of the astronauts—one of them, Victor Carroon, stumbles out, but there are no traces of his compatriots anywhere in the rocket, and no signs that the doors had ever been opened before the landing. While Quatermass fights with the London police, who want to butt in and investigate what happened, Carroon is hospitalized, only able to speak in rare gasps, unable to describe what happened, and showing various physical symptoms of some mystery condition, his skin pulsating and his silent attention wandering. The first big hint that something is afoot comes from the police’s sneaky attempts to get Carroon’s fingerprints, and after receiving the entire crew’s vital statistics from an angry Quatermass, they find that not only has Carroon’s fingerprints changed, they seemingly contain specific traits from the fingerprints of the other crew members.

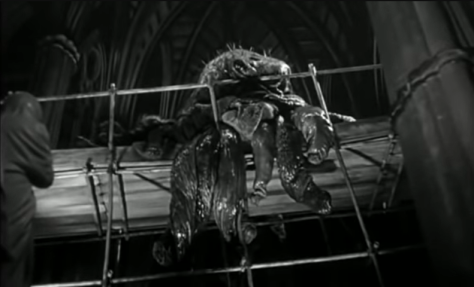

We’re dealing with some strange and gnarly sci-fi here: while in the void, the rocket ran into an extraterrestrial entity that drifts around in space, and in the process it merged with Carroon and then proceeded to absorb the other two astronauts into one body. Dealing with a very literal case of multiple personalities, Carroon’s physical form eventually begins to act out the alien organism’s instinctual need to feed, sucking out the juices of every living thing around it (beginning with a potted cactus), and he eventually melts down into a blob of congealed DNA. The climax has the glob hiding out in Westminster Abbey as Quatermass and the police enact a plan to destroy it.

Watching both the two episodes of the serials and the movie, the change in format is highly noticeable—the entire first episode of the original is basically covered in five minutes in the movie. While that means Xperiment gets to the central mystery a lot faster, I do appreciate the detail and texture found in the serial—in the second episode, we get much more of a reaction from the local yokels who suddenly find a crashed rocket in the middle of their house, and little details like interviewed witnesses thinking it might be a nuclear bomb (and a man immediately outside with an “End is Nigh” sandwich board) help sketch out the wider world of the story. Not surprising for something that was six episodes long, the teleplay included a lot more business, including a tenacious journalist trying to uncover the story, and a group of foreign agents that kidnap Carroon before he really begins to mutate. While the streamlining of the story in Xperiment is appreciated, it does lack of some of the character depth and ideas that TV allowed: Carroon’s wife goes from a major character in the serial (where she was a mathematician working with Quatermass) to a more traditional worried spouse who facilitates Carroon’s escape but disappears once he turns full monster; they do more with the idea that Carroon carries the memories of the other crew members; and the ending is changed quite dramatically, with the serial having Quatermass convince the three human minds in the monster body to rebel and force it to self-destruct, while the movie employs a much more direct, violent method. The latter of the three changes apparently arose partly from writer/director Val Guest (who would go on to direct Quatermass II and The Abominable Snowman) thinking that Donlevy’s version of the character would not be able to make a plea to the human spirit as convincingly as Tate’s.

This is not that surprising, as Donlevy’s brusque and forceful Quatermass does come off as sort of a jerk at times. He certainly seems like someone who could brute-force a successful manned rocket launch, but his frustration with the people around him seems less like a scientist making breakthroughs than as a private business owner annoyed by people interfering with his work. His refusal to reconsider his scientific endeavours in the face of the horrors he’s witnessed, seen especially in his conversations with Carroon’s wife and in his final lines, do have a feeling of stubbornness to it. In the two episodes of the serial we have, Tate seems a bit more level-headed and idealistic, although he still demonstrates a similar frustration with all the ignoramuses getting involved in this scientific story.

Xperiment’s main calling cards are its atmosphere, created with a shadowy cinema verite style, and the main performance by Shakespearean actor Richard Wordsworth (who is, in fact, related to nineteenth-century English poet William Wordsworth) as Carroon. In the two extant episodes of the serial, we have only a scant glimpse of Carroon, well before most of the actual monster drama starts, but it would difficult to top Wordsworth’s mostly-silent performance, playing a man who has the look of someone trapped in permanent anxiety and pain, knowing that his body is no longer his own but unable to do anything about it. Carroon is played for both sympathy and horror, a victim who nonetheless poses a real threat to everyone around him, and the way he shifts from his pained look to the middle-distance stare that precedes his acts of violence are memorably haunting. The movie also has the benefit of more elaborate make-up effects by Phil Leakey (who would follow this with X the Unknown and Hammer’s first few Dracula and Frankenstein movies), giving Carroon distressingly translucent skin, pulsing veins and a half-cactus hand, making him look as if he is progressively falling apart as the movie progresses…which, as we learn, he essentially is. The full alien monster seen at the end was constructed by noted effects man Les Bowie (in the serial, the effect was evidently created by Kneale himself using a plant-encrusted glove) from tripe, and while a big blob may seem conventional, this is another blob that existed before blob movies became a regular thing, and the final form has a certain horrifying quality after watching human Carroon’s deterioration throughout the rest of the movie—it helps that it has a big human eye, as well as a disturbing human scream when it dies. At no point are we meant to forget that this monster is technically just some really unfortunate person.

Carroon’s story is what really sets this apart, and what defines Kneale’s approach to science fiction. The recurring theme in much of his work is that the universe is full of terrifying things, or at least things beyond our puny human comprehension (as in the more sympathetic Abominable Snowman), and he’s interested in showing learned people (and the rest of the world) bumping up against them. Rarely do these stories deal with straightforward antagonistic alien forces, as there’s always something much more deeply troubling about what they are and what they represent, posing an existential challenge to humanity—this is especially true in the stories that deal directly with human history and evolution like the equally influential Quatermass and the Pit (but let’s save the discussion of that for another day.) In Experiment, we see someone whose very physical existence has been warped entirely by accident, by something unearthly and borderline incomprehensible even to a scientist like Quatermass. The disturbing cosmic horror found so frequently in Kneale’s work immediately stood out from other Sci-Fi of the early fifties, especially in visual mediums, and the viewers who noticed it carried it with them—aside from being a major influence on the BBC’s own Doctor Who (which Kneale himself considered a straight rip-off), one of the most famous acolytes of Kneale is John Carpenter, who often displays a similar Gothic worldview in his movies. Carpenter is such a fan of Kneale that he used the pseudonym “Martin Quatermass” and even got Kneale to write an early version of Halloween III: Season of the Witch, an experience that Kneale himself had nothing good to say about. If you couldn’t tell from all these stories, Kneale was kind of a beligerent person.

Of course, Quatermass proves in the end that scientific rationality and human spirit can overcome even these bizarre disasters, although that’s not to say that there isn’t a critical eye towards the sciences present in these stories—Donlevy’s Quatermass might actually be closer to Kneale’s cynical viewpoint than you’d think. Victory does not arise without some casualties, and not without the lingering knowledge that such horrors exist out there. We are shown that as humanity enters the space age, we will run the risk of encountering those things that go against everything we know, the products of an irrational universe. If fifties monster sci-fi often leans hard into a sense of paranoia about the world, Quatermass represents a paranoia of a much greater scope.