Before the name The Terminator defined what a blockbuster film would be for the ensuing thirty years, and before it became synonymous with a lurching franchise constantly finding new ways to not justify its own existence, The Terminator was, simply, a monster movie made by former Roger Corman employees (and with Joe Dante’s Gremlins released a few months before, 1984 was a pretty good year for monster movies made by former Roger Corman employees.) But what could have been a small and economical film with the simple hook of “someone being chased by an unkillable monster” instead feels large in scope, something that does not want to be contained by the Corman ethos. Largeness would come to define pretty much every movie by James Cameron, who started out as a special effects technician, had the frustrating experience of being micromanaged on Piranha II (a sequel to a Corman-produced monster movie directed by, guess what, Joe Dante), and then came up with this and guaranteed the rest of his career. His technical ambitions logically flows from his time in the effects and art departments, but there’s a vision here that isn’t just tailored to fit an effects vehicle—an approach to how to make a thriller, an atmosphere, a sense of what makes for particularly potent “cool” imagery, all stuff that has been normalized in genre movies now but definitely feels distinct when compared to the movies I’ve been watching from this period recently. Everything here comes together in such an explosive way, and casts such a long shadow over film as a whole, you often forget that, at its heart, it is a horror movie, following and innovating on a long line of horror movies.

This movie was famously taken to court by influential sci-fi writer Harlan Ellison for borrowing one of its core concepts from his Outer Limits episode “Soldier”—the idea of two soldiers from the future going back in time and engaging in a destructive battle—and Ellison ended up paid off and given special thanks credits across the series, much to Cameron’s consternation. In fact, much of this movie seems derived from sources across history of technophobic Science Fiction: Skynet takes the conceit of 1970’s Colossus: The Forbin Project and updates it to the age of Reagan’s “Star Wars” defence program; the idea of humanoid robots made to infiltrate human enclaves was in Philip K. Dick’s story “Second Variety” (which was later adapted into the movie Screamers); and you saw a movie about someone being chased by a homicidal robot, complete with RobotVision®, in Westworld (which is why I wrote about that one first.) So, yes, this is a synthesis of other people’s ideas, but it feels like a culmination of its influences rather than just a rip-off, playing off those established concepts and otherwise creating a very different world for them to inhabit.

It also feels like a response to where the horror genre had gone in the early eighties, taken over by the legion of slasher movies churned out in the wake of Halloween. Generally, those movies also deal with seemingly invincible murder machines who chase after suburbanites and get right back up at the most inopportune moments, and they had more or less supplanted monster movies as the go-to source of genre-based mayhem. The rebuttal provided by this movie is twofold: those hulking killers were merely men, where here we are dealing with a being of pure Sci-Fi invention (although early on Paul Winfield’s police lieutenant suspects that they’re dealing with just another gimmick serial killer); and the slashers preferred the animal savagery of knives and other sharp implements, while this one uses the more modern and somehow even more blunt force of massive firepower. The Terminator follows the format of a slasher in places—complete with final girl—but it revels in putting in the big, fantastical ideas that those films generally lacked (such as time travel and killer robots, the kinds of things movies used to be about), and also in looking expensive just as those movies flaunted their frugality.

Another big innovation is, of course, the person playing the monster. Arnold Schwarzenegger was known at the time this movie was made—he had already been Conan the Barbarian, and played him again around the same time as The Terminator—although he was not yet the eighties movie star Arnold that he would become immediately following this, which means the presence he exudes in this movie is different than the more jocular one he specialized in later. From the moment he first appears on screen, gigantic and naked as all get out, the movie knowingly frames his mountainous body shape to make him seem completely inhuman long before his battle damage brings out the Stan Winston special effects (which remain iconic, even if the stop motion robot and dummy Arnold heads stand out as classically cartoonish). This was apparently a problem early on for Cameron, who noticed what would become an endearingly ludicrous trend in Arnold’s movie roles: he is often cast as characters who are meant to be at least nominally normal and inconspicuous when that is literally impossible for him to be. But while he can never be the stealthy “infiltrator” that the Terminators are supposedly meant to be (a vision that would be more fully realized with Robert Patrick’s T-1000), as a much simpler conception of something imposing and implacable that you certainly wouldn’t want to be chased by, he is perfectly used, effortlessly embodying the mechanical ruthlessness of the AI assassin in a way only his particular acting style could achieve. It’s the kind of ceaseless menace—some of his only slightly touched-up glares are more imposing than the image of metallic death he becomes in the climax—that his later career as the archetypal action hero would never allow him to pursue again.

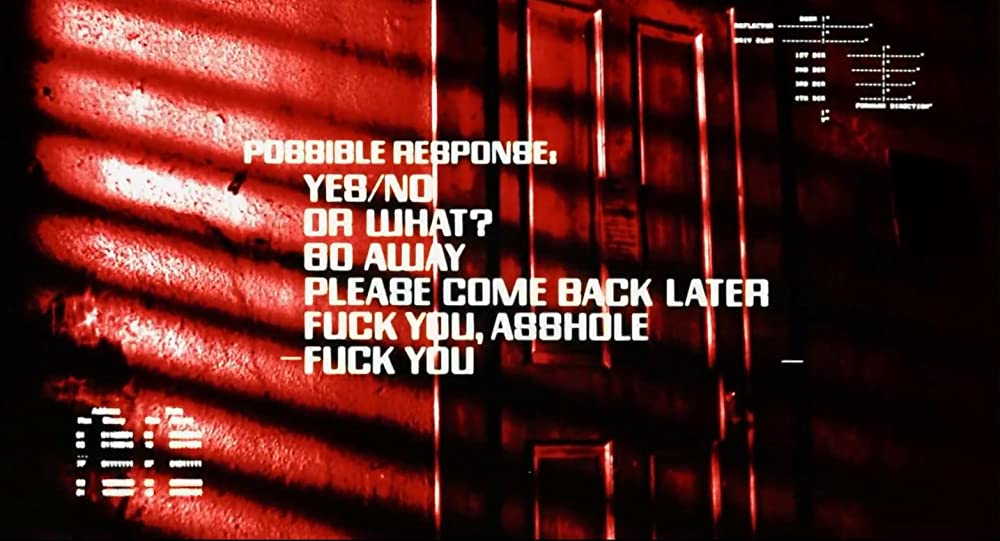

The way this murder machine is written also finds an interesting balance between efficiency and the sheer brute force of a thing built to plow through everything to reach its goal. Sometimes, this comes off as hilariously contradictory—he’s a robot that can imitate specific human voices, knows when to duck out to repair its disguise (with a pair of cool shades), and has a list of exactly which guns to get, but who will also just blow away the gun merchant (played by Dick Miller, showing that this isn’t that far from the Corman camp) in broad daylight, and the sheer crudity of systematically killing every Sarah Connor in the LA phone book seems a bit over-the-top for what’s supposed to be an advanced AI. The famous “I’ll be back” scene is built on the dark comedy of the robot finding a light impediment and answering it with extreme force. On the other hand, that makes it far more chilling, a robot that really doesn’t care how it goes about getting its target, mass violence seemingly just a function—one of the scenes from Kyle Reese’s future warzone shows another Terminator going about its business with an equal level of proficient brutality. Despite the great lengths to make them look human, in the end these are not much different from the robotic planes and tanks we also see stalking the wastelands of the future—all for the better for a movie looking to justify elaborate action set pieces.

This also brings up just how The Terminator evolves the killer robot form set up by Westworld a decade earlier. Yul Brynner’s Gunslinger obviously formed the template for a stalking nemesis that cannot be reasoned with or even really stymied, but the underlying theme of Westworld is that it’s human technology that is malfunctioning. This, on the other hand, shows a human creation that is working all too well, coming to its decision of complete extermination from a seemingly rational interpretation of its purpose—our technology turning against us as an active decision rather than just a random error, and building its own intelligent products for the express purpose of carrying it out (if you look at the more influential monster movies of the eighties, you’ll find a recurring trend of taking the fears of older movies and ratcheting them up to fit an even more anxious age.) That was the cynical modern update of the genre: humanity’s downfall is no longer an accident, and the sense of inevitability provided by the time travel angle gives it an even bleaker edge.

(It’s also noteworthy that while Brynner’s robot was built to be a throwback to another time and genre, Arnold’s look in this will always be peak eighties, as is almost everything in this movie, from the hair to the synth score that is likely a big inspiration to many video game soundtracks. )

It also goes a step further in updating one of Westworld‘s other innovations, focusing on regular people—you still had to pay money to go to Delos and be chased by a robot, giving the horror has a level of distance for the audience, but in The Terminator the robot comes to you in your own home, finally making the killer robot genre truly universal. This is decision that is helped immensely by actually being filmed in Los Angeles, a real urban landscape filled with as many realistic denizens of 1984 as it is slightly exaggerated 1984 movie characters (like gang of knife-wielding punks, among whom is Cameron go-to Bill Paxton—you’ll also find future Aliens/Pumpkinhead star Lance Henriksen in here as well.) It’s also immensely helped by the performance of Linda Hamilton as Sarah Connor, who goes through a borderline fairy tale character arc where someone enduring lower-middle class mediocrity becomes saviour of humanity, while also going from traumatized target to action heroine—Hamilton/Sarah reacts realistically to having a metallic monster always at your back, but by the end she is the one who destroys it (complete with quip), transitioning between these modes with surprising ease and without really sacrificing the humanity she had in her early scenes (Michael Biehn as Kyle Reese basically serves as the monster expert, someone who is on hand to explain the genre concept, and gives the role a survivalist’s mixture of emotions.) All of this brings in just enough realism that it makes the utter cruelty of its violence hit even harder, and you become invested in it all to a degree that some of the more obvious cliches of its finale—the monster rising up after its apparent destruction and a chase through a steam-filled factory—don’t even register.

Those moments are where the movie’s spiritual connection to other monster movies become the most apparent, and where I could see its roots in the more modest genre films of its time (for all their ambition, the effects-laden moments, have a certain quaintness to them that still anchor them in this era of genre film.) But Cameron is never known to do things by halves, so those moments are wedged between elaborate car chases and a relentlessness that drives the entire movie—this is something that takes the shape of horror/monster movies but through its emphasis on action has quite a different feel, as well as a grand design that synthesizes many different genres (it’s no surprise that when its direct sequel got even more money to utilize, it chose to pursue the possibilities of that design.) There’s a grand apocalyptic vision here that, much like its robotic antagonist, it’s willing to smash through every barrier to reach.