What makes Ray Harryhausen’s stop motion work stand out is his attention to lifelike detail. Following on the techniques of his mentor, King Kong animator Willis O’Brien, the animated creatures in his movies have tics and behaviours that mimic those of real animals, no matter how outlandish or fantastical the creature is. They make the kinds of seemingly pointless movements that living things have, and they react dynamically to situations—all the kinds of things that lesser animation and guy-in-suit movies generally lack (although they sometimes make up for it with unique performances), but with the same “physical object” gravity that all practical effects possess. Yes, these days his animation no longer has the “realism” that they once touted, especially when seen in a level of fidelity they were never intended for, but there’s a sense of empathy that comes through Harryhausen’s work, a sense that these things have a vitality and a presence, and aren’t just there for schlocky thrills, which is why in interviews he never liked his creations to be called “monsters.” Remember, too, that for most of his career, he did all that painstaking frame-by-frame animation by himself—it’s a true labour of love.

Of course, the history of monster movies really begins with the desire to bring dinosaurs back to life—that’s what built O’Brien’s career, and Harryhausen followed dutifully. As I’ve said elsewhere, dinosaurs are like every imaginary monster humanity has ever concocted, except they were real animals that roamed this planet in a time so long ago, it was more or less an alien world. Artists have been trying to resurrect them visually ever since Richard Owen coined the term in the nineteenth century, and when film came around, suddenly we had the opportunity to see these long-dead organisms move around (based on our current knowledge of how they moved around) for the first time. O’Brien was the master of the movie dinosaur, and nothing could match the marvel of his work on King Kong, but he never really got a chance to work on that subject again during his unfortunately turbulent career—it was appropriate, then, that Harryhausen would see one of his unrealized dinosaur-based ideas come to fruition years after his death. That would be The Valley of Gwangi, which probably felt like a bit of a throwback when it was released in 1969, and was under-seen at that time (because the new management at the studio gave it paltry advertising, at least according to Harryhausen himself), but did prove to be a bit of a benchmark when it came to portraying dinosaurs on-screen.

If one were to describe Gwangi as “King Kong with Cowboys”, they’d be pretty accurate, I’d say. The idea of combining prehistoric creatures with horse-ridin’ and lassoin’ had previously been filmed in the 1956 film The Beast of Hollow Mountain, which was in fact based on O’Brien’s pitch for Gwangi (another one of his pitches, which would have seen a boy and his pet bull fight a dinosaur, sounds delightful), but you know, a novel concept can still be pretty novel the second time through. Similarly to Harryhausen’s fantasy epics, I’m sure the idea of having a monster movie without defaulting to modern city mayhem and military responses was a big appeal—this is a much simpler set-up, and with its high-spirited soundtrack, it feels the part of a western.

Set in Mexico, all the troubles start with a travelling circus whose staged “cowboy and Indian wars” and horse diving acts aren’t pulling in the numbers like they used to. One potential solution comes from protagonist Tuck Kirby (TV actor James Franciscus), a sly huckster who has returned to convinced the circus’ star, and his one-time lover, TJ (Gila Golan, overdubbed because her Israeli accent was too thick) to sell her horse, and later the entire circus; the other potential solution is the circus’ secret new act: a tiny prehistoric horse (an eohippus) comically called El Diablo. TJ’s plan is to have the small horse ride around on the back of a normal horse, you see. As we learn, El Diablo was supplied by a man named Carlos, who left his Roma (which is, of course, not the term they use in the movie) community to join the circus and got the horse from his dying brother. who had ventured into the “Forbidden Valley.” What makes that valley so forbidden? Well, according to the band’s matriarch Tia Zorina (Freda Jackson, who we previously saw heavily mutated in Die, Monster, Die!), that’s where Gwangi dwells, and anyone who steals from it is cursed. The situation also pulls in paleontologist Professor Bromley (Laurence Naismith, who had also interacted with Harryhausen effects in Jason and the Argonauts), who is out to find evidence that humans evolved earlier than thought, which is a stupid hypothesis that he absolutely does not prove and he ends up sidelining because of a completely unrelated discovery, working with the Roma and Tuck’s kid sidekick-for-hire Lope to steal the mini-horse specifically so he find out where this valley is.

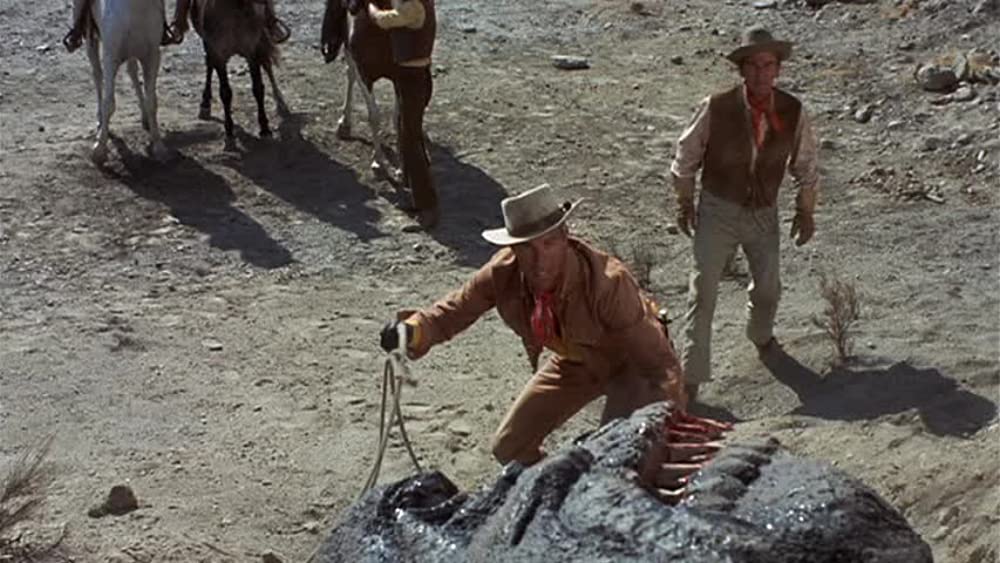

So, eventually they all go to the Forbidden Valley, which isn’t very well forbidden (it also has worse ranch dressing than Hidden Valley), and guess what? There’s dinosaurs in that thing as well as small horses (of course, as we know now, Mexico would probably be the last place you’d find surviving dinosaurs.) Honestly, given who they share the space with, those eohippus got a bad deal. Aside from a pteranodon (which gets its neck snapped by Carlos) and a styracosaurus, there’s also Gwangi itself, which supposed to be an Allosaurus but is really just a smaller T-Rex, who ends up getting knocked out by a landslide while pursuing our human cast and is then taken to be the big new attraction for the circus. Sounds great, nothing could possibly go wrong with that idea.

The characterizations in this movie are a little strange. At first we’re supposed to take Tuck as morally ambiguous given the way he apparently broke TJ’s heart due to his bad boy nature, and he is constantly under the watchful eye of the circus ringleader (Creature From the Black Lagoon and It Came From Outer Space star Richard Carlson) but they pretty quickly reconcile and he then decides he’d rather get a ranch in Wyoming and also married—as well, TJ starts off fairly pure, but as soon as they have Gwangi she becomes all about they money, until suddenly she isn’t. While a little self-serving, the Professor and Carlos are not really shown in a negative light (Carlos is actually quite heroic), and Tia Zorina’s warnings not to mess with Gwangi are clearly correct, even if their choice to free the dinosaur in the middle of a show was probably not a great idea—so when the mayhem starts and many of those characters are killed off one way or another, it feels strangely merciless. In fact, once Gwangi inevitably escapes and things go wrong, it’s surprising just how wrong they go, and even leads to some dark comedy moments with the circus’ music band. Much like in Kong, this is a bad situation for everyone and they should have known better.

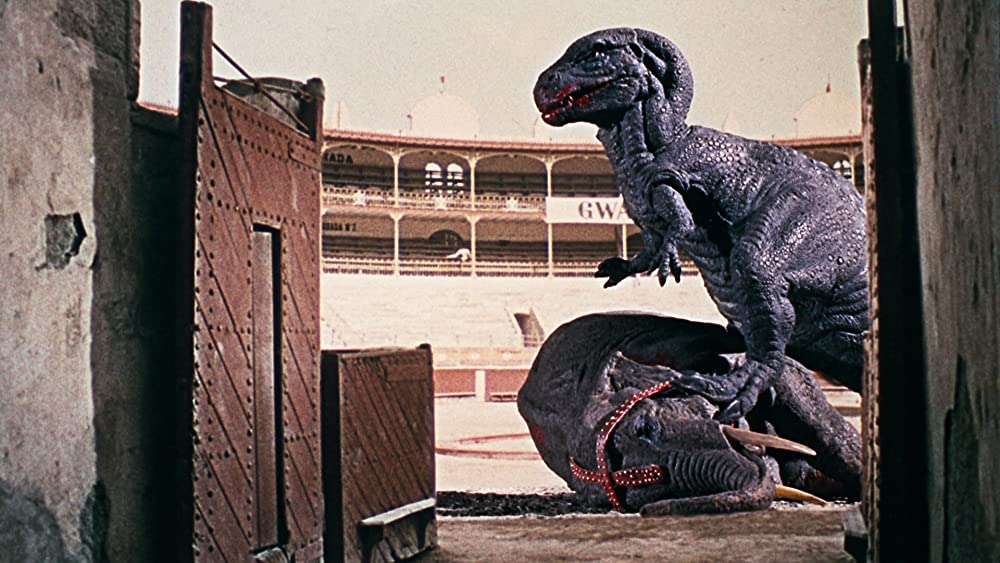

But that’s really only the wrapping on this thing—the point is to see Harryhausen animate dinosaurs, and quite a few different ones. There are always ambitious compositing feats included in his movies, and in this case we get to see the pteranodon interact mostly seamlessly with the humans (which also includes a few moments with an actor punching a puppet) and the stand-out scene of the cowboy crew, which includes guys named Bean and Rowdy as all crews should, roping Gwangi, which probably required as much coordination as the skeleton sword fight in Jason and the Argonauts. Gwangi’s entrance is also great—appearing out of nowhere to chomp on a smaller dinosaur (a moment that is likely referenced in Jurassic Park)—and the movie definitely does not skimp out on stop motion creature-on-creature battles, with the star dino fighting both the styracosaurus and later a circus elephant (sort of a repeat of the alien vs. elephant fight from previous Harryhausen FX showcase 20 Million Miles From Earth) that makes sounds that are definitely not elephant sounds. As in all Harryhausen’s effects work, there is a real sense of life to the portrayal of the dinosaurs here (as well as the eohippus, which does just as much interacting with the human cast), especially when they’re on screen together acting as an ecosystem and not just as a threat to the actors, that makes them seem believable even if their appearance and exact behaviour do not match current scientific understanding. I wouldn’t say they have an “inner life”, but they do seem to have a sense of purpose outside just serving the plot, like we’re observing their regular existence before a movie rudely interrupts it. That’s also why it’s entirely appropriate that Gwangi gets an “And” credit in the end. Absolutely deserved, that guy put in the work.

It also helps that the location filming in all those sprawling badlands, shot mostly in Spain, gives the movie a sense of naturalism and scope (this in spite of the fact that live action director Jim O’Connolly apparently didn’t care much for the project), making it into a King Kong-like story with a unique visual marker. This is a movie that ends with a dinosaur running around an ornate cathedral, which is probably not something that you’ve seen in a lot of movies. Speaking of that, when that church burns and takes the Gwangi with it (the fire is probably among the iffier effects), the only one in the crowd shedding a tear is Lope—I’d think seeing the local church destroyed would probably induce a wider and stronger response than that in the local population.

Most would probably find Harryhausen’s work in the fantasy genre overall more enjoyable for their epic scope and sheer imagination, but for a genre mash-up that’s it a bit (a bit) more grounded in nature, Gwangi is still still a fairly colourful and low-key wondrous—you don’t get to see prehistoric life portrayed with this much care that often. There’s a long distance between Gwangi and the next stage of dinosaur movie evolution, so it held a place in the hearts of all the dinosaur-loving sorts who actually managed to see it, and clearly inspired those later productions. It’s impact on the genre is not as immediate and obvious as King Kong or even Harryhausen’s earlier movies, but it did subtly evolve the way the terrible lizards were portrayed, advancing it towards a sense of treating them as animals and not just as mindless monsters. I’m sure Willis O’Brien would have been pleased.