The late Larry Cohen may be the perfect B-movie director: someone who has no problem utilizing the absurdity found in the more disreputable genre films, with wacky premises and bizarre special effects and actors putting in heightened performances, in order to make something both memorable and meaningful. His films look dumb on the surface, but are full of inspired creative choices, comedic touches, and a devotion to pursuing ideas no matter how weird they get, producing movies that I don’t think anyone else could. This is the freedom one is allowed in those disreputable genre films, if you know how to work within certain limits.

While working in many genres, Cohen’s monster movies stand out for their particularly dogged combination of schlock and big ideas—Q and The Stuff are some of the most unique entries in the entire genre, hilarious and anchored by actors going all out to portray the kinds of characters you never really see in these types of movies. The heights of Cohen’s career are very much apparent in It’s Alive, his first foray into the realm of creature features, beginning with its simple, silly, and imaginatively fertile high concept: what if you had a baby, and your baby was a monster? The idea of a killer baby would probably be enough for people who just want to see some violence, and enough for it to be dismissed out of hand by people with good taste, but what’s amazing about this movie is how much it actually focuses on the social and emotional fallout of the situation, and especially the effects it has on the parents of the terrible infant. There’s an appreciable human centre to this off-the-wall pitch, and that’s the Larry Cohen difference.

In order to effectively twist the knife, the movie begins with much happy-go-lucky mundanity and seventies suburban colour: Frank and Lenore Davis (John P. Ryan and Sharron Farrell) excitedly go to the hospital for the birth of their second child (even their eleven-year-old son is looking forward to it), and in the waiting room the high-spirited Frank gets into a conversation with other fathers-to-be, representing a gamut of masculine types—although the conversation does go to some weird places, like the state of the planet. The hints of something going wrong are subtle: every once in a while, Lenore shows signs of discomfort despite otherwise being in a chipper mood; before leaving to stay with his uncle while they are away, the son asks Frank if it’s possible that his mom could die during childbirth, which Frank tells him is the sort of thing that doesn’t happen anymore; and, of course, the actual birth ends up taking more time than expected, although the doctors assure Lenore that there’s nothing abnormal about it. What happens after that, though, is the most abnormal thing possible—Frank goes into the delivery room and finds all the medical personnel dead in bloody heaps, while their baby is missing. As over-the-top gruesome as it is, it’s also stomach-churning imagery that taps into every parental nightmare possible.

Once the police and the hospital staff are involved, there is absolutely no question about what happened: the Davis’ newborn was a bloodthirsty mutant, and has escaped, and while Frank and Lenore are at first hard-pressed to truly believe that, everyone else (which, as it turns out, also includes the news media) already knows what’s up. The plot is refreshingly to the point, so we can get to what it’s actually about, which in this case is continuing to poke at a worst case scenario for parents, both in the situation itself and in the way that other people react to it. As soon as Frank leaves the hospital, he hears the story being reported on the radio and, in what feels like a real breach of journalistic ethics, he and his wife are openly named, which begins a long string of insensitivity and outright cruelty aimed at them. Reporters swarm Frank to ask questions that he couldn’t answer even if he wanted to, the nurse hired to look after Lenore (who is put on a load of medication, which renders her alternatively dreamy and paranoid) secretly tries to tape record her, a doctor from the hospital keeps in constant contact and gets Frank to sign away ownership of the infant’s body for scientific study, and when Frank tries to return to his PR firm he basically gets the Kirk Van Houten cracker factory treatment from his fake-friendly boss. The situation is so bad that they try to keep their son in the dark as much as possible, which means he can’t watch TV or even go to school, in case the crowds pick him out as the brother of the monster baby. The only person who seems remotely sympathetic to them is the police lieutenant, who tells them that he and his wife are also expecting. Despite being victims of the situation as well, the sheer coldness and suspicion that the Davis’ are greeted with creates this troubling atmosphere of cynicism, and we are reminded that there are indeed monsters other than fanged babies that rip peoples’ throats out.

We get a handful of moments with the monster baby, almost all of them shot from its POV as it crawls around suburban LA and murders random passersby, including a milkman, because of the irony you see. It’s pretty clear that it’s a budgetary/logistical thing, as there’s really no way for them to show an infant jumping around murdering people in ways that won’t make this ridiculous movie even more ridiculous, and most fleeting shots of the baby we see are pretty obviously an adult in a mask (the adult in question being the wife of special effects master Rick Baker), which for some people might actually make it more creepy. To be honest, I found that the only real creepy things about the baby are the sounds it makes—groaning mixed with some lightly altered infant noises—which are unnerving, and become even more so the further into the movie you get. Cohen focuses on creative shots that leave more to the imagination, such as objects on a floor being moved (every location has a cluttered, lived-in quality), while the moments when the baby attacks people are often a dream-like jumble of jump cuts and inserted footage. This is especially jarring during a moment near the climax of the movie, where a shot of a baby puppet chewing on flesh is intercut with a shot or two from earlier in the movie. The absurdity is probably played up to an extent, such as in the scenes where the police raid a school (but still look in dark corners by themselves, demonstrating that they’ve apparently never seen a movie before), but there are fewer outright comedic moments than in Cohen’s subsequent films, although the two standouts (the police surrounding a normal baby, and a cop trying to use a child-height water fountain) are pretty good.

While it would probably be a stretch to call the characterizations of Frank and Lenore after the incident “realistic”, I think they are recognizable anxious performances, both trying to find ways to avoid addressing the trauma. The real focus of the movie is on Frank and his patriarchal worries, his attempts to emotionally distance himself from the situation (claiming that the baby “isn’t his”) coming not just from the horror at hand, but by the idea that the baby’s aberrational nature is somehow his fault. Frank signing away the infant’s body without Lenore is part of this, as is all the times he inserts himself into the police investigation (why the police let him do that, I don’t know) and everyone (including his wife) susses out that he feels he needs to be the one to kill the baby in order exorcise his perceived masculine shame. There’s no real reason for us to think that he is in any way responsible—the origin of the baby’s mutation is left ambiguous, with radiation and adaptive evolution (conflating the conversation about the environment Frank had at the hospital with an exterminator’s anecdote about cockroaches adapting to his pesticides) floated as possibilities, but with the most focus put on a contraceptive medication given to Lenore by the jerk doctor, which in turns leads to a scene where he is asked by a rep from the medication’s manufacturer to make sure the baby is destroyed so no medical examination can take place. Even so, his perception of being made a pariah is probably a more effective emotional journey, and that journey works because John P. Ryan really nails his portrayal of this fraught person, who despite the silly nature of the concept really comes through as a believably aggrieved father. Sharon Farrell’s loopy hysteria is also effective, but the wife is not given nearly as much screen time in this, so she does not get to be seen as nearly as complex. You could probably make an interesting variant of this movie that focuses entirely on the mother (has someone done that yet?)

(Fun aside: Ryan would go on to do a voice in Batman: Mask of the Phantasm, while the police captain in this is played by Michael Ansara, the future voice of Mr. Freeze on Batman: The Animated Series.)

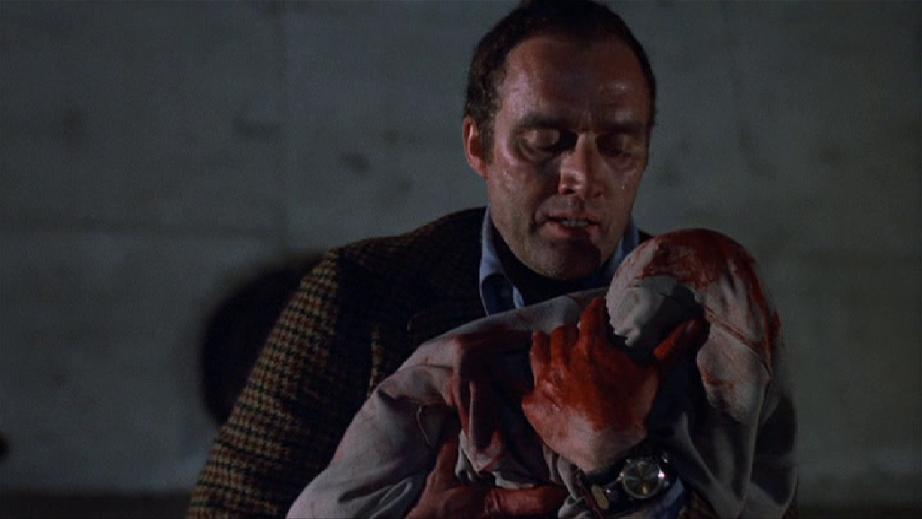

This all plays out in a surprisingly gripping finale, which goes where you don’t expect. From the get-go, it is telegraphed that Lenore actually wants her baby back, and we eventually establish that the thing is looking for its family (which is why it goes to its brother’s school), so we are not shocked that she eventually lets it into their home, a revelation that maybe takes a bit too long to play out. Frank ends up shooting it after it kills the uncle (but pointedly does not attack their son), and the police and him end up following the trail of its blood to the LA sewers, a setting that is possibly an homage to the giant ant movie (and inevitable Creature Classic subject) Them! But when Frank finds the baby huddling in those pipes, he can’t bring himself to kill it, and finally acknowledges it as his child in a scene whose emotional nature maybe overrides the fact that it’s a scene between a father and his killer monster baby. In an otherwise violent and cynical movie, love and family bonds are still very much in play, and it makes for a surprisingly touching and tragic ending. Ryan should get all the credit for this, especially since he is essentially acting against nothing.

That a movie with such trashy trappings could end up acknowledging the humanity in its characters is just a testament to Cohen’s peculiar and endearing strengths as a writer/director. Like I said, I can’t imagine anyone else would tackle this subject in this way, if they would tackle this subject at all. While It’s Alive doesn’t reach the monster schlock spectacle heights that later Cohen movies would indulge in, as a story it is well up there with the rest, and makes me further appreciate what we had when we still had Larry around.