Where the previous Roger Corman movie I wrote about benefited from a more character-based approach that made up for a fitful distribution of monster scenes, its follow-up goes in the complete opposite direction, intentionally paring the script down to primarily scenes about the monster at its centre and simplifying characters so they are defined only by their jobs, genders, or accents (hilariously, screenwriter Charles B. Griffith, a frequent Corman collaborator who will be showing up in future posts, explained that “[Corman] said it was an experiment. ‘I want suspense or action in every scene. No kind of scene without suspense or action.’ His trick was saying it was an experiment, which it wasn’t. He just didn’t want to bother cutting out the other scenes, which he would do.”) At around 63 minutes, Attack of the Crab Monsters barely makes feature length (but is even more perfect as part of a double feature), and while maintaining much of the feel of a fifties creature feature, its maniacal pace and devotion to “suspense and action” makes itself felt off the hop—we get a decapitation within the first five minutes, after all. Even aside from that, what would seemingly be a typical example of one of the fundamental types of narrative conflict—man against man, man against self, man against giant radioactive crab—is complicated by said giant radioactive crabs acquiring some truly bizarre characteristics, giving them an unexpected presence throughout the movie. This is a case of something appearing routine on the surface but having a truly peculiar imagination when you peer into the tidal pool.

Played out by a cast of Corman regulars and the Professor from Gilligan’s Island, the story follows a group of scientists sent out to an obscure island in the Pacific that bore the fallout of the Bikini Atoll nuclear tests to continue the work of another group of scientists who mysteriously disappeared, which is only a mystery to someone who has never seen a movie before. With the exception of the disappearances, a sailor being decapitated, a rescue plane suddenly exploding, and the island hosting absolutely no life outside of crabs, everything seems perfectly normal until a surge of tremors begins to reshape the entire island, prompting questions. There’s a journal left behind by one of the previous scientists, but it’s so fixated on talking about an unseen Attack of the Worm Monsters that it proves to be of very little help. Unexpectedly, the answer to all those questions turns out to be “a giant crab did it”, but not just any sort of giant crab—a giant crab whose exposure to radiation loosened its atoms to such an extent that not only did it get really big, and not only is its body so vaporous that bullets go right through it, but that it now absorbs the minds of beings that it eats. Among the advantages it gains from this is the ability to speak in the voice of its human victims, which it uses to lure away the other members of the crew who rarely question where the voices are coming from.

You might not notice that intentional script streamlining at first, because many of the required scenes for this type of movie are present, gradually ramping up to the crab monster attacking. But when you pay close attention, you begin to clue in to the fact that there is no real downtime or tangents at any point—if the characters are having a conversation, it is entirely about the events of the story. There are no subplots or character arcs, and the relationships between everyone here are strictly professional (except for the male and the female leads, but it’s not like you get much romance between them in any case.) Despite the exotic location, there are once again a bare minimum of sets (and I’m not entirely certain that the cabin they’re staying in is not the same cabin that was in Day the World Ended with the furniture rearranged.) Just about the only shots that arguably linger are the scuba-diving scenes, which seems like one of those extravagances that Corman wanted to get as much out of as possible. It’s really not until near the end of the movie that you realize that no scenes do not in some way relate to the crab monsters, and then the magic trick of how this thing is only sixty-three minutes reveals itself. Once the final crab monster attacks have been dealt with, the movie promptly ends, as without any crab monsters, there is nothing left to discuss.

Anyway, as you can see, this is another “radiation is magic” movie (which, according to Griffith, was required by Corman), but one that makes the “radiation turns animals in Satan” angle from Day the World Ended look logical by comparison. By throwing in some nonsense about electrons and atoms that the audience has no time to think about (because it’s already moved on to another scene of suspense or action), they infer that these crabs have essentially become beings of pure energy that have just assumed the form of giant crabs and can incorporate the electronic impulses of the human brain into themselves, forming some sort of biological gestalt. That means they can talk, I guess telepathically (and sometimes through the radio), but it also means they can learn—at one point, the lead crab picks up the knowledge of how to use dynamite. They can still have their limbs taken off, though, and one of the two crab monsters is defeated by having a rock lodged in its brain. Thankfully, the solution to the attacking crab monster problem is a little more interesting than that.

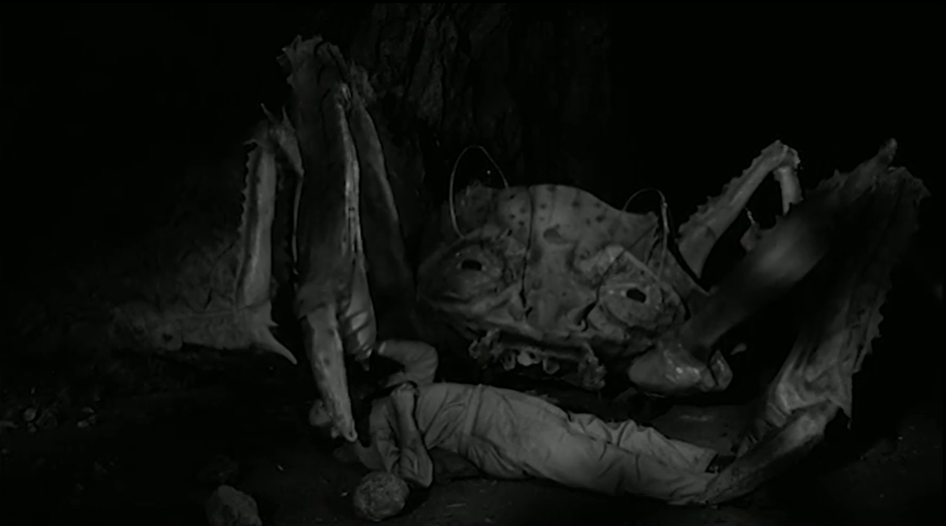

That all sounds very high concept, and it is, but it’s also completely ludicrous. The thing is, that it’s the kind of ludicrous that manages to have a genuinely unsettling undercurrent—the very idea that these man-eating monsters can speak in not just a human voice, but in the human voice of your friends and colleagues, is a pretty terrifying concept, something that I could see haunting a monster-loving kid seeing this in theatres or as part of a random horror movie package on TV years later. I mean, when you hear your parents’ voice behind the door, how can you be really sure it’s them? I can also imagine that concept benefited from having two characters with over-the-top European accents—one French (who also has his hand severed, the other moment of surprising violence in this), one German—so you have a giant crab threatening you by swapping between distinctive voices (it is charmingly goofy when it starts tossing off those threats, for example stating that while it can regrow a claw in a day, “Will you regrow your lives when I have taken them from you?”) Also straddling that funny/fear-inducing line is the giant crab puppets, with their large human-like eyes being one of those indelible design decisions that give character to entirely unbelievable, dated effects. Which is good, because we see a lot more of the monsters in this then in the Day the World Ended, and the crabs do a lot of killin’ here—the pacing of when they kill off the less-than-nobody characters and the ones who we see more often (but are still two-dimensional at best) means that we are kept pretty off-balance about who is actually going to make it to the end of the movie, and that it turns out to be the most obvious group of good-looking normies doesn’t take that ambiguity away, I don’t think.

They also go for a sense of claustrophobia here, with the cast regularly noting that they don’t know how they’re going to get off the island (the crab knocks out the radio for a time, although we still get some moments where they tune into a “local” radio station for some Polynesian ditties), and taking stock of how the landscape is contracting as the crabs crack at its foundations. The gradual disintegration of the land, giving them less and less room in which to avoid the crabs, is another genuinely inventive way to give the horror some psychological heft, and one that can ratchet up over time as the cast and the number of locations dwindle. It’s also another one of those sleight of hand filmmaking tricks that Corman pulls off, because our actual view of the landscape is so controlled that they can imply the island is sinking only through the power of suggestion. When one character points out to some expanse of ocean and says that a cliff used to be there, we can only take their word for it. This is another one of those things you probably won’t notice until the very end of the movie, and pure Corman economy in action.

There isn’t really a lot to grapple with in the narrative of Attack of the Crab Monsters, which is fundamentally as silly a B-movie as its title implies, and with all the human interest surgically removed in order to better serve the silly B-movie aspects. As well, its approach to the nuclear question is so utterly distanced from reality that looking for subtext there is a fool’s errand—it was an aesthetic arising from its time, that’s all. But from a structural and conceptual standpoint, it makes it mark through that hyper-efficient scripting and filming, which could either be seen as dumbing it down or simply taking out a bunch of story beats that wouldn’t have been that interesting anyway, and through its devotion to taking the common atomic monster idea and just going for it. Certainly, there were enough giant animals created by radiation in the movies, but rarely did they get this kooky, which is one of the true joys of B-movies. This movie is more representative of the tone Corman aimed at for the rest of his monster movie output from this period, less serious than Day the World Ended, and soon to become even more self-consciously wacky.