We’re back covering streaming movies, and this month’s focus will be on Shudder, an entirely horror-focused service. Considering how ubiquitous horror movies are, it’s pretty apparent that a large number of them are still beyond the acceptable palate of the mainstream—cheaper-looking, bloodier, more disturbing, or just plain weird—so a place like Shudder fills a useful niche by giving the seedier and more extreme ends of the genre a home. It also includes many pieces of important horror movie history, which is what we’re going to start with—and I’m talking way back in history, too. Yes, it’s about time I covered a silent film.

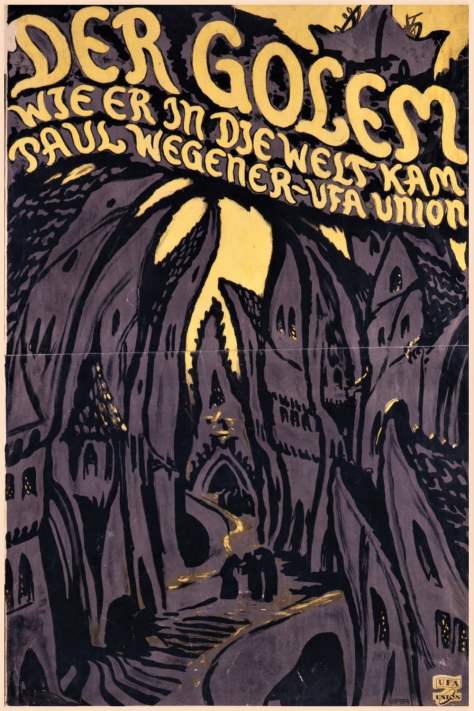

Generally, my goal with this series is to focus on lesser-known monster movies—but The Golem (subtitle How He Came Into The World) from 1920 is actually a very influential film, helping to popularize German Expressionism alongside classics like The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (which was released the same year) and Nosferatu. Defined by stylized, dream-like sets with mammoth, crooked scenery enveloped in looming shadows, the kids these days might know German Expressionism as that thing Tim Burton kept trying to imitate. But aside from its part in that movement, The Golem is also a genre-defining monster movie (made before that genre of film, or maybe any genre of film, even existed), which very clearly inspired later movies, especially the Frankenstein series Universal made a decade later. In fact, the movie’s cinematographer, Karl Freund (who also shot Fritz Lang’s Metropolis) would later fulfill the same role on Universal’s Dracula, and then directed The Mummy—so the lineage down from The Golem is pretty direct, even if it’s not talked about as much anymore outside of hardcore film history circles. That Shudder wanted it as part of their line-up just shows how much they care about showcasing the entirety of that history—and they keep the presentation pretty traditional, quite unlike the time I saw a cable TV showing of Nosferatu using Rob Zombie tracks as the background music.

Co-written, co-directed, and starring Paul Wegener, The Golem is an adaptation of the legend of Rabbi Loew of Prague, who was said to have brought a clay golem to life in the late sixteenth century to protect the Jewish people from persecution and violence. After first appearing in Germany in the nineteenth century, this is the story that brought the concept of the golem into the public consciousness, with this film (which is actually the third Golem film Wegener made, but the only one that still exists in complete form*) further popularizing it. As the film opens, Loew (or Löw, as it’s written in the title cards) spies star formations that portend disaster, which is immediately corroborated by a message from the Holy Roman Emperor decreeing that the Jews are to be vacated from their ghettos. Loew’s response, of course, is to secretly build a golem, and then call upon the demon Astaroth (represented by a creepy, smoke-spewing mask) to give him the magic word that will bring the golem to life, which is written down and stored in a star medallion on the thing’s chest. At first, Loew uses the golem as a servant, much to the concern of everyone else in the ghetto, but later brings it along to a demonstration for the Emperor, where it saves his life (after one of Loew’s magic tricks literally brings the house down) and convinces him to pardon the Jews. Meanwhile, one of the Emperor’s knights has a secret affair with Loew’s daughter, and when the rabbi’s assistant (who is also in love with her) finds out, he unleashes the golem as revenge, but loses control of it, almost burning down the whole ghetto as it kidnaps her and goes on a rampage.

The first striking thing about this movie is, of course, the look of it—while it doesn’t have as much of the mind-bending design of Caligari, there’s a scale (the ghetto’s primary door consists of both a smaller and a larger one, a detail that is almost King Kong-esque) and jaggedness to visuals of the Jewish quarters, both indoor and outdoors, that provide a similarly unique touch. Many things in that place seem to have a stony quality to it, matching the golem’s complexion and contrasting it with the ornate appearance of the Emperor’s throne room (which seems to be right across the one bridge, as we see it crossed many times by different characters) and the fancy dress and foppish manner of the Emperor’s crew (who can’t even watch a magic movie about the Wandering Jew without laughing uproariously at it and getting the movie mad at them.) It’s impressive that something could seem so large at certain moments and positively cramped in others, with a suffocating preponderance of darkness that gives something like the demonic invocation scene an unnerving quality that remains a century later. Considering that the movie is that old, it has an inherently ghostly quality to it that probably enhances a modern viewing of it.

You also get a lot out of Wegener’s performance as the golem, which is both mysterious and menacing in its own right, but also presages much of what you’d see in later monster movies like Frankenstein. As soon as the golem opens his eyes, his expression is a little blank but not empty—he spends much of his early appearances observing things and loyally following orders, but you always get the impression that he could take a turn at any moment—and when he does, at first by showing a sense of self-preservation and then by going full on aggressive with a malevolent snarl on his face, it feels both inevitable but still a bit shocking, mainly due to the way Wegener emotes. Of course, the golem is driven to it only because others misuse him, but he also never comes off as a sympathetic being if only because he goes utterly berserk at the drop of a hat, leering at the rabbi’s daughter as he carries her off (one of the first examples of that in a movie?) or dragging her around by her long braids, and chasing down and murdering the Emperor’s knight before setting Loew’s home on fire (I did find it amusing that Loew’s daughter and assistant are rather nonchalantly relieved that there was no trace left of the dead man’s body, absolving them of having to explain anything.) So, despite obviously inspiring the portrayal, the golem never has the audience appeal of Boris Karloff’s Frankenstein monster—and his final scene, where is confronted by and deactivated by a little girl, almost feels like a comical inverse of Frankenstein’s most famously tragic moment, even though it predates it by several years.

There’s also something powerful in the narrative, and the way it mythologizes real world history. The golem is a product of desperation, created using dangerous methods because Rabbi Loew sees no other way of protecting his people when they’re at the complete mercy of the Christian majority, who show little to no respect for them and can apparently can just kick them out of their homes whenever they want (with the reason given being essentially “because you exist.”) Throughout the film, Loew, as played by Albert Steinruck, has a look of turmoil and pain, knowing that what he is doing is ultimately a necessary evil, one that he at first has to hide from everyone else. That he and his golem are able to get the pardon without necessarily resorting to violence is miraculous, and he is rightly celebrated by his peers for it—but he also knows that once the task is complete, the golem must be destroyed to avoid it being corrupted by the dark powers that animate it. It’s a selfless burden he takes on for the good of his community, and it is only when his creation is used irresponsibly by his assistant that it goes from guardian to true monster (or, maybe, a force of nature.) I’m sure when the story was told and retold among the Jews of Europe, it was seen as both an inspiring call for resistance (something they probably needed on a constant basis), as well as a cautionary morality tale about hubris and messing with forces you can’t control.

The Golem remains a stunning tale told simply and beautifully, and once again, I appreciate that Shudder includes it among the more modern gore-fests, even if it’s the only film of its vintage currently featured. Kids gotta learn their horror history somehow, and Wegener and co.’s work here forms the basis from which most subsequent creature features derive. It stands out in a lot of different ways among the stuff they offer, and not just because it’s the oldest, either.

*According to Wikipedia, the original plan was for Wegener to make a movie featuring both the golem and famous German novel femme fatale Alraune, which I think would have been the first-ever team-up of famous horror characters, predating Frankenstein Meets the Wolf Man by over two decades.